BSides Brisbane 2023 - Writeups (Part 1: crypto, rev, IoT)

The BSides Brisbane CTF was an exciting mix of traditional jeopardy challenges, and hardware/enterprise hacking. Huge props to the team who made this top quality CTF happen!

Unfortunately I didn’t have enough time to properly try out all of the IoT challenges and enterprise hacking challenges available, but at least I got to solve one of the IoT challenges, one of the perks of an in-person CTF :)

Overview

I could just make the write-ups about my solutions, but I like to also include the process I followed because that’s often a lot more valuable than just a solve script. I also hope that it shows you that some challenges just take a lot of persistence!

- Hard(ly) encryption (crypto - 100 points)

- Neo (crypto - 300 points)

- crackme (rev - 150 points)

- Cafeteria (rev - 300 points)

- Rogue Transmitter (IoT Village - 400)

Hard(ly) encryption (crypto - 100 points)

While walking around the office during a red team engagement, you notice the following printed out on a piece of paper left on a keyboard: \x3c\x5d\x2e\x29\x4b\x69\x7f\x63\x77\x58\x3c\x63\x5e\x5e\x44\x1c\x39\x43\x36\x3e\x44\x5e\x11\x4c

You also note the following on a postit note taped to the monitor of the same desk: Z1ON0101

Can you work out what this means?”

Author: bman

At first I thought it could be something similar to the Vigenere cipher because that’s simple and takes a key. Nothing else came to mind, so I started messing around in Python trying to implement the Vigenere cipher but with bytes instead of the alphabet. After a few minutes I hadn’t found anything promising so I put the ciphertext into CyberChef hoping that maybe the Magic recipe would magically tell me something useful (it didn’t 😅).

As I was looking through the script again I remembered that XOR existed (which I should’ve remembered much earlier due to the challenge description and the random looking bytes in the encrypted message). I quickly modified the script to perform XOR ‘decryption’ and sure enough, the flag popped right out.

To save time at the end I could’ve used CyberChef’s Unescape string recipe (to interpret the hex character codes) followed by the XOR recipe, which is good to know for next time.

Flag: flag{XOR-is-not-crypto!}

Neo (crypto - 300 points)

Help! I’ve forgotten the password to this old encryption service that’s running on a server I no longer have access to. All I have is the source code and a copy of the encrypted password from when I used it last year :( Can you help me find what I changed the password to?

Author: deluqs

We’re provided with a Python program, and an encrypted password (along with its corresponding IV). The provided program has two commands; Encrypt a message, and Login. The encryption used is AES in CBC mode with a 16 byte block size and pkcs7 padding (this becomes important later).

Luckily I had been reading about CBC padding oracle attacks the day before the CTF so that’s the first thing that came to mind. And spoiler, it turned out to be a padding oracle challenge :)

Padding oracle attacks

A padding oracle attack is possible when CBC mode encryption is used and there is a way for an attacker to verify whether a given ciphertext has valid padding when decrypted or not. Usually this comes in the form of an API endpoint that has different error messages that distinguish between invalid decrypted contents, and invalid decrypted padding. In our case, it’s a Python program running over TCP which we can interact with over netcat (as is usual for CTF challenges).

I’ll do my best to briefly explain padding oracle attacks as I go, but I recommend reading this writeup for a cryptopals challenge for the best explanation of padding oracle attacks I’ve found so far! I ended up taking and modifying their exploit script when I couldn’t get mine to work (I really wanted to write it myself but I also wanted to be fast cause of the CTF).

What we’re working with

KEY = # redacted

password = # redacted

def encrypt(message, IV):

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_CBC, iv=IV)

padded = pad(message, 16, style='pkcs7')

return cipher.encrypt(padded)

def decrypt(message, IV):

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_CBC, iv=IV)

decrypted = cipher.decrypt(message)

unpadded = unpad(decrypted, 16, style='pkcs7')

return unpadded

def login():

try:

print("Enter the IV:")

IV = b64decode(sys.stdin.buffer.readline().rstrip())

print("Enter the encrypted password:")

ciphertext = b64decode(sys.stdin.buffer.readline().rstrip())

plaintext = decrypt(ciphertext, IV)

if plaintext == password:

# ... print flag

else:

print("Access denied.")

except:

print("Error: malformed message")

def encrypt_message():

print("Enter the IV:")

IV = b64decode(sys.stdin.buffer.readline().rstrip())

print("Enter the plaintext:")

plaintext = b64decode(sys.stdin.buffer.readline().rstrip())

ciphertext = encrypt(plaintext, IV)

print(b64encode(ciphertext).decode("utf-8"))

while True:

print(f"Choose an option:\n0: Encrypt a message\n1: Login\n> ", end='')

choice = int(sys.stdin.buffer.readline().rstrip())

if choice == 0:

encrypt_message()

elif choice == 1:

login()

else:

print("Invalid choice!")

Figure 1: important parts of the provided script source code (simplified for brevity).

I’ve simplified the script by removing some unrelated input validation and such, but for the purposes of our exploit the functionality is the same.

The most important thing to notice is that invalid padding will cause Error: malformed message, and an incorrect password (with valid padding) will cause Access denied.. This is essential for a padding oracle attack.

The program expects IVs, ciphertexts, and plaintexts to be inputted as base64.

Writing the exploit

First we need to set up a way for the solver to interact with the service to check whether a given ciphertext’s padding is correct when decrypted (Figure 2). This can be done by using pwntools to interact with the program, and then checking which error message we get. This primitive is called the oracle, and it’s all the information that the solver needs to fully decrypt the ciphertext 🤯.

from base64 import b64decode, b64encode

from pwn import *

SUCCESS = 0

ACCESS_DENIED = 1

MALFORMED = 2

BLOCK_SIZE = 16

iv = b64decode("ORYo2QThghEvpHv+wD3D6w==")

ciphertext = b64decode("01jm3AZpstbCZ3WQwbNAsQ==")

p = remote("neo.crypto.ctf.bsidesbne.com", 3302)

p.recvline()

def login(iv: bytes, password: bytes):

p.recvuntil(b"> ")

p.sendline(b"1")

p.recvuntil(b"IV:\n")

p.sendline(b64encode(iv))

p.recvuntil(b"password:\n")

p.sendline(b64encode(password))

response = p.recvline()

if response == b"Access denied.\n":

return ACCESS_DENIED

elif response == b"Error: malformed message\n":

return MALFORMED

else:

print("key:", response.decode("utf8"))

return SUCCESS

def oracle(iv, password):

return login(iv, password) != MALFORMED

Figure 2: harnessing the oracle 🔮.

Next (and this is the part I took from the handy article) we can crack the plaintext byte by byte. To understand this part we need to take a look at the PKCS#7 padding scheme. Say we have the plaintext abc and we need to pad it to 4 bytes. The only valid way to do this with PKCS#7 is to add a byte of value 1 to the end of the message to get abc\x01. And if we needed to pad it to 5 bytes, we would have to add 2 bytes of value 2 to the end of the message to get abc\x02\x02. You always add n bytes of value n to the end of the message to make it the desired length. In the context of this challenge, the message will get padded so that its length is a multiple of 16 (the block size). If the server decrypts the message and the padding doesn’t follow that scheme, it’ll return the Error: malformed message error message. Importantly, messages always need to be padded up to the next multiple of the block size, so if a message is already 16 bytes, it would need to be padded out to 32 bytes to avoid ambiguity.

The padding scheme on its own isn’t particularly useful to us, but when combined with CBC encryption and a padding oracle, it is. To encrypt the plaintext that we’re given the ciphertext for, the server first padded the message to 16 bytes with PKCS#7 padding, and then it encrypted it with a CBC mode cipher. In the single block case which we’re working with, CBC essentially just XORs the plaintext block with the IV block and then encrypts the result with AES encryption. To decrypt the message, CBC will decrypt the ciphertext with AES encryption, XOR the result with the IV, and then check the padding. The idea of the attack is that we can figure out what the output of the AES step is by influencing the XOR step through the IV and observing whether the padding is correct or not. First we go through all possible final bytes for the IV and see which ones result in valid padding. This will yield one or two valid values. One of them will be the original value of that byte of course (we already know that it’s valid), and if the message wasn’t already padded with 0x01 the other value will be the value that XORs to produce 0x01. We want to know which of these values produces a final byte of 0x01 which we can find out by modifying the second last byte of the IV (see the script). Once we know which value produces a final plaintext byte of 0x01, we can XOR it with 0x01 to find what the last byte of the output from the AES stage was! We can now calculate what value for the final byte will result in 0x02, and then try all possible values for the second last byte of the plaintext to find which one will produce a value of 0x02 (resulting in the valid padding \x02\x02). We can continue this process until we know every byte of the output of the AES step! XORing this with the IV (as CBC does) we can finally recover the original plaintext. If I lost you in there somewhere, go check out the article I’ve referenced too many times, they explain it in much more detail!

# ...

# Source: https://research.nccgroup.com/2021/02/17/cryptopals-exploiting-cbc-padding-oracles/

def single_block_attack(block, oracle):

"""Returns the decryption of the given ciphertext block"""

# zeroing_iv starts out nulled. each iteration of the main loop will add

# one byte to it, working from right to left, until it is fully populated,

# at which point it contains the result of DEC(ct_block)

zeroing_iv = [0] * BLOCK_SIZE

for pad_val in range(1, BLOCK_SIZE+1):

padding_iv = [pad_val ^ b for b in zeroing_iv]

print("Working on %d" % pad_val)

for candidate in range(256):

padding_iv[-pad_val] = candidate

iv = bytes(padding_iv)

if oracle(iv, block):

if pad_val == 1:

# make sure the padding really is of length 1 by changing

# the penultimate block and querying the oracle again

padding_iv[-2] ^= 1

iv = bytes(padding_iv)

if not oracle(iv, block):

continue # false positive; keep searching

break

else:

raise Exception("no valid padding byte found (is the oracle working correctly?)")

zeroing_iv[-pad_val] = candidate ^ pad_val

return zeroing_iv

# Source: https://research.nccgroup.com/2021/02/17/cryptopals-exploiting-cbc-padding-oracles/

def full_attack(iv, ct, oracle):

"""Given the iv, ciphertext, and a padding oracle, finds and returns the plaintext"""

assert len(iv) == BLOCK_SIZE and len(ct) % BLOCK_SIZE == 0

msg = iv + ct

blocks = [msg[i:i+BLOCK_SIZE] for i in range(0, len(msg), BLOCK_SIZE)]

result = b''

# loop over pairs of consecutive blocks performing CBC decryption on them

iv = blocks[0]

for ct in blocks[1:]:

dec = single_block_attack(ct, oracle)

pt = bytes(iv_byte ^ dec_byte for iv_byte, dec_byte in zip(iv, dec))

result += pt

iv = ct

return result

print(full_attack(iv, ciphertext, oracle))

Figure 3: using our oracle to crack the plaintext byte by byte.

This script can successfully crack the ciphertext given a minute or two (most of the time is spent communicating with the oracle). The plaintext turns out to be Mr@nd3r5oN2022\x02\x02. Given that the challenge wants us to figure out what the creator changed their password to, Mr@nd3r5oN2023 would be a very good guess. An excellent guess in fact 😅. Logging in presents us with the flag.

Flag: flag{yOu-n3ed-T0-sE3-th3-0rAc13}

Solution: solve_neo.py

Conclusion

Overall a very well made challenge! I enjoyed the final touch of having to ‘guess’ the new password, it added a bit more personality to the challenge. I’ve only recently started getting into crypto (the good kind), and this only made me want to learn more!

crackme (rev - 150 points)

I wrote the following program to calculate the flag. It takes a bit, please be patient.

Author: deluqs

A good place to start with these kinds of challenges is to simply run the program to see what it does. This gives us more context and can speed up the reverse engineering process (although for a challenge like this that doesn’t really matter).

$ ./crackme

Please wait for the flag to be calculated :)

Figure 4: running the crackme.

Nothing to really see there, so let’s take a look at the decompilation using Ghidra.

void main(undefined8 param_1,int param_2) {

char extraout_AL;

int local_10;

int local_c;

puts("Please wait for the flag to be calculated :)");

for (local_c = 0; local_c < 0x23; local_c = local_c + 1) {

for (local_10 = 0x1f; local_10 < 0x7e; local_10 = local_10 + 1) {

encrypt((char *)(ulong)(uint)(int)(char)local_10,param_2);

if (extraout_AL == DATA[local_c]) {

putchar(local_10);

}

sleep(300);

}

}

return;

}

void encrypt(char *__block,int __edflag) {

return;

}

Figure 5: the crackme decompiled using Ghidra.

The first thing to notice is the sleep(300) line which runs every single iteration of the double-nested loop. Waiting 5 minutes every iteration is bound to slow things down a tad 😅. The other thing to notice is that although Ghidra seems to reckon that the encrypt function is empty, it’s actually not (which I can tell from looking at the assembly view). It seems to be multiplying its first argument by 0xffffffa7. However, I digress, we’re here to speed up the program, not fully reverse engineer it.

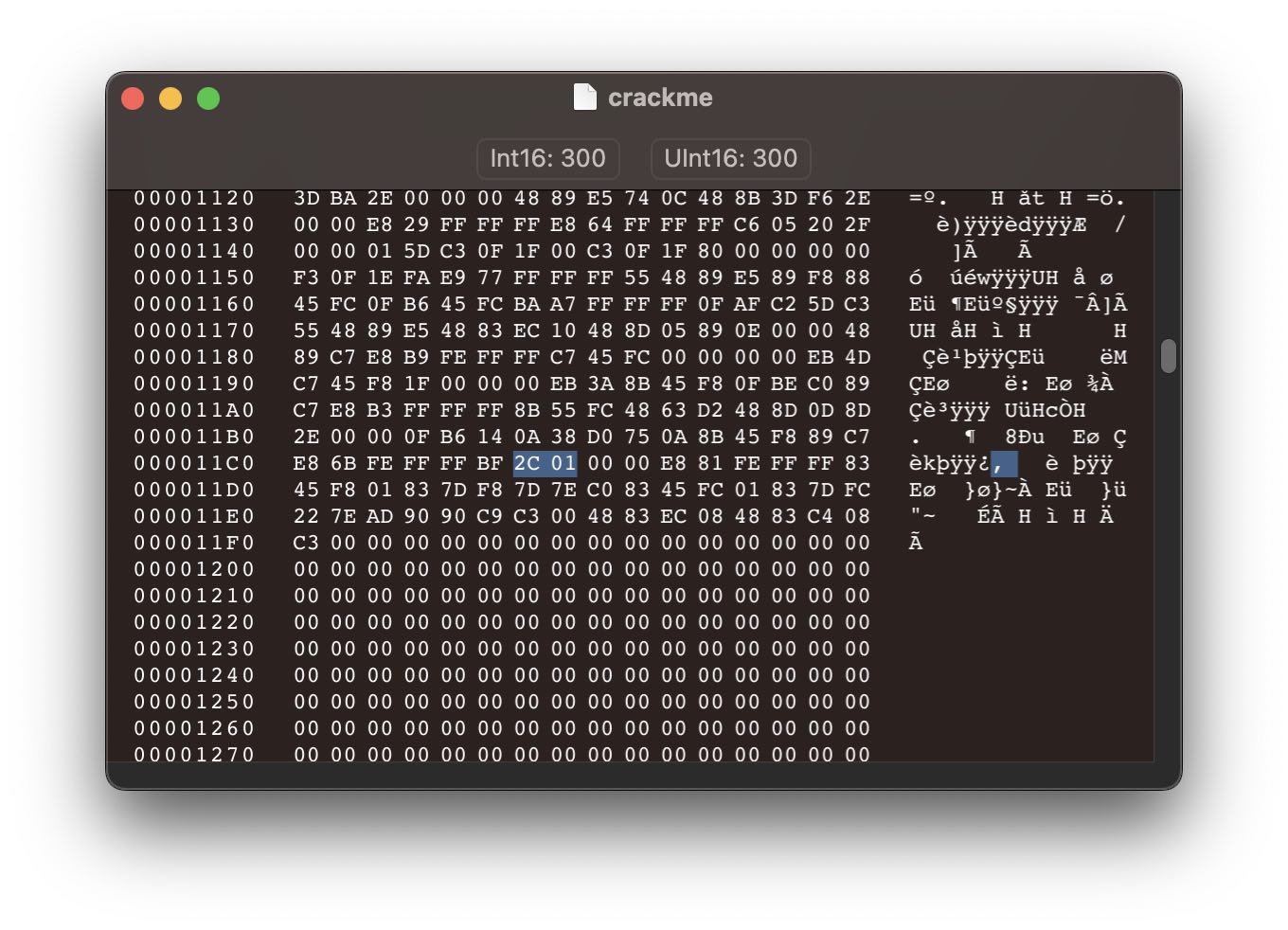

To remove the sleep we’ll need to patch the binary, which isn’t as tedious as it sounds if you have a solid plan. There are two main ways we can go about patching out the sleep; we can either replace all related instructions with nops (which do nothing), or we can change the duration from 300 to 0. I usually find the second approach easier because 300 (0x12c) will be easier to spot in a hex editor than some op codes. It also doesn’t involve googling what the op code is for nop which is nice.

First we need to locate the value that we’re going to patch. To do so, click on the sleep(300) line in Ghidra and the assembly view will highlight the related instructions.

...

001011c5 bf 2c 01 MOV EDI,0x12c

00 00

001011ca e8 81 fe CALL <EXTERNAL>::sleep

ff ff

...

Figure 6: disassembly of the instructions related to sleep(300).

First, 0x12c gets moved into the edi register (which is where the first argument to a function is usually placed), and then sleep gets called. Note that 0x012c is stored in the machine code with its bytes reversed because of endiannes, but that doesn’t matter for us because all we need to do is replace both bytes with 0x00!

Now time to hop into a hex editor; I use Octets on macOS, but any old hex editor will do. You could even use this online hex editor (which I’ve never used, but it looks like it’s good).

Figure 7: the bytes we need to change (displayed in a hex editor).

Figure 7: the bytes we need to change (displayed in a hex editor).

All we need to do now is backspace these two bytes and replace them with 00 00. After saving the file we can now run the program and get the flag basically instantly!

Flag: flag{aint-nobody-g0t-time-for-d@t}

Cafeteria (rev - 300 points)

The cleaners packed away the chairs and tables and I forgot how they were layed out. Can you help me figure out a layout that fits the our constraints?

Author: deluqs

This is a classic rev challenge where we have to figure out valid inputs to get the flag. After connecting to the service with netcat we’re asked where the chairs and tables should be put. Putting in a for both at least tells us that the program expects 0s and 1s to denote where the chairs (and tables) should be placed.

> nc cafeteria.rev.ctf.bsidesbne.com 1337

Help me cram as many people into this cafeteria as possible!

Where should I put the chairs?

a

Where should I put the corresponding tables?

a

Please 0's and 1's to denote where chairs are

Figure 8: giving the program some dummy input.

Next lets take a look at the program in Ghidra. Interestingly, when I opened a fresh copy of the program in Ghidra to make the write-up, Ghidra decompiled it differently 😅 (and better). The overall structure of the program can be deduced by reading the strings passed to puts at different points in the code.

- Use

getsto read two streams of0s and1s from the user corresponding to the layouts of chairs and tables respectively (into buffers that Ghidra reckons are 140 bytes and 128 bytes respectively, in reality they’re both 126 bytes as evidenced by the following loop). - Iterate through the two strings to convert them from an ascii binary string to an array of integers (consisting of only

0s and1s of course). Do so for 126 bytes of each. - Check whether any chairs or tables are on top of the bins. The bins are hardcoded to be at offsets

0x1d0and0x1d4, which correspond to indices0x1d0 / 4 = 116and0x1d4 / 4 = 117respectively (the array elements are 4 bytes each). - Check whether any chairs and tables are in the same spot.

- Check that every chair is next a table.

- Check that there are at least 20 chairs (more than

0x13). - Print the flag if all checks pass.

With that information in mind I basically just went with my first instinct: 20 alternating chairs and tables (20 of each).

from pwn import *

# alternating chairs and tables

chairs = b"10" * 20

tables = b"01" * 20

# pad to required length with 0s

chairs = chairs.ljust(126, b"0")

tables = tables.ljust(126, b"0")

p = remote("cafeteria.rev.ctf.bsidesbne.com", 1337)

p.sendline(chairs)

p.sendline(tables)

p.interactive()

Figure 9: my solution script.

And there we go, we get the flag printed after the ASCII art visualisation of our layout

> nc cafeteria.rev.ctf.bsidesbne.com 1337

Help me cram as many people into this cafeteria as possible!

Where should I put the chairs?

101010101010101010101010101010101010101000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Where should I put the corresponding tables?

010101010101010101010101010101010101010100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Your cafeteria layout. '#' is a table, '.' is a chair, '@' is a rubbish bin:

------------------

|.#.#.#.#.#.#.#.#.#|

|.#.#.#.#.#.#.#.#.#|

|.#.# |

| |

| |

| |

| @@ |

------------------

flag{op3rat1ons_r3se4rch_i$_co0l}

Figure 10: successfully solving the cafeteria challenge.

Flag: flag{op3rat1ons_r3se4rch_i$_co0l}

Conclusion

Overall a nice challenge, but I’m surprised it only got 4 solves! I think rev/pwn tend to scare people away sadly.

Rogue Transmitter (IoT Village - 400)

In-person the challenge was simply an antenna sitting on top of a platform in a pelican case (which wasn’t to be fiddled with). The challenge description (which has since left my mind) was something like this:

One of our office radios has been make weird transmissions every few minutes and we believe that it might be being used to exfiltrate data. See if you can tap the transmission and decode the message.

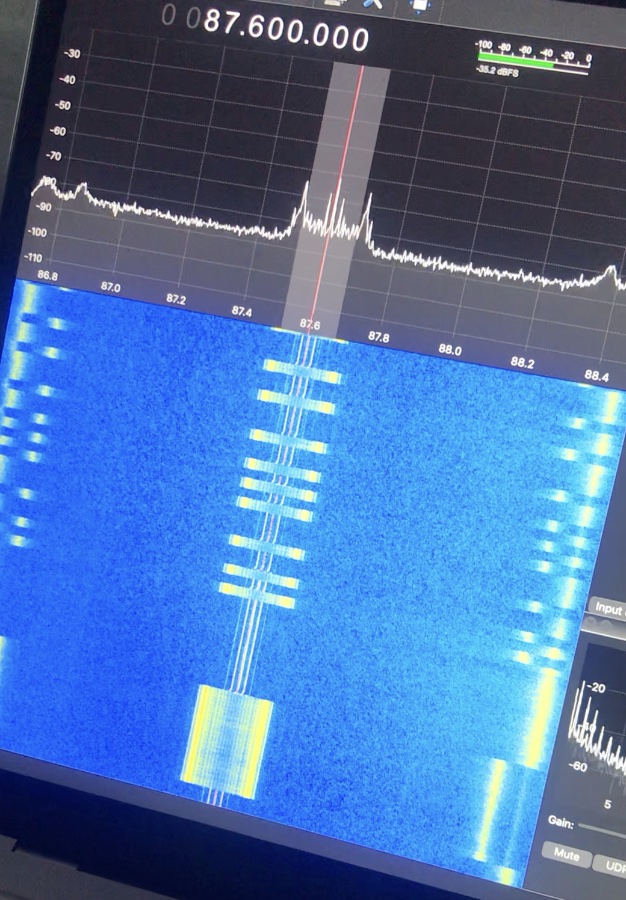

Luckily I had a software defined radio with me which I could use along with GQRX (a GUI for software defined radios) to solve the challenge. Arguably GQRX isn’t the best app out there, but it’s the one I had used in the past so it’s what I went with. I’ve heard that Universal Radio Hacker is a much better tool for the job. If you’re looking to get a software defined radio, I can definitely recommend the RTL-SDR (although it seems to be quite a bit more expensive than I remember).

The first order of business was to figure out what frequency the message was being transmitted on, so I started from the lowest frequency supported by my software defined radio and started slowly increasing the frequency and stopping whenever I saw anything mildly interesting. Eventually I came across a frequency which had a very weird looking signal. I was lucky that the message was being transmitted as I scrolled past because otherwise I might’ve had to scroll through quite a few times 😅. Talking to the challenge creator afterwards, I found out that generally there’s only a small number of frequency ranges that you actually have to check because the rest aren’t legal to transmit in.

Figure 11: i didn’t take a screenshot, so a screenshot of a video of the screen will have to do.

Figure 11: i didn’t take a screenshot, so a screenshot of a video of the screen will have to do.

Given that the frequency was so wide, slow, and digital, I was pretty certain that I had found the right frequency (any real transmissions would be a lot faster). The frequency was around 87.6kHz.

After waiting for around 8 minutes for the current transmission to finish and the next one to start, I decided to just video my screen as the transmission happened (because I hadn’t figured out how to record properly in GQRX fast enough).

I noticed that all of the blips in the transmission were the same length but there were 3 unique sizes of gaps between the blips. My first thought that the transmission could be using morse code (with the smallest gap representing a dot and so on). Typing out the resulting morse code into a translator yielded garbage. Next I started researching simple signal encoding methods and found nothing other than morse code and other very similar encoding methods.

Later in the day the challenge creator (Josh) told us that the word tap in the challenge description was meant to be a hint (very subtle to be fair), which pretty quickly led me to discover tap encoding, a way of encoding messages with fixed length ‘taps’, perfect!

.. . ... . . . .. .. .. ... . . . ... . ... . . ... . ...

. .... .... .. ... . ..... .... .... .. ... .. .... ... ...

.. .. .... ...

-> flaghaccallthethings

Figure 12: translating tap code.

And there we go!

Flag: flag{haccallthethings}

Conclusion

Woohoo! Probably one of the coolest challenges that I got the chance to try, purely because I’ve never done anything like it before :)